Testing low fidelity (lo-fi) prototypes is a cost-effective, time-efficient, and versatile way to understand what is fundamentally important to users. This article discusses the value of lo-fi prototype testing, and why it should be integrated into the design process.

What is a Low-Fidelity Prototype?

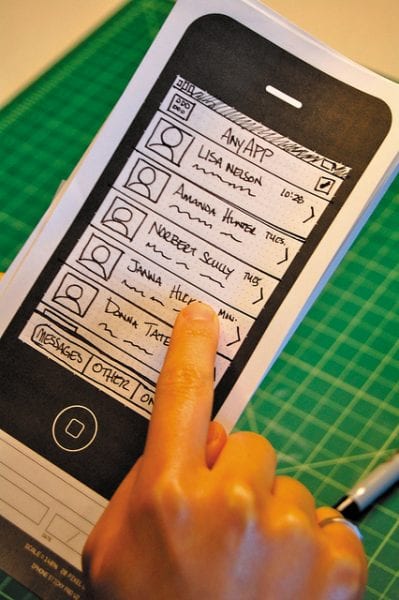

A lo-fi prototype is a basic representation of a product or service which simulates the intended interaction between the user and the product or service.

This could be as simple as the paper prototype seen in this video.

In digital user experience research, lo-fi prototypes can be as simple as a series of sketches on paper. They can also be clickable prototypes built in advanced software such as Axure, InVision, Sketch, and Adobe XD; however the idea is to keep concepts unrefined and loose allowing users’ imagination to ‘fill in the blanks’.

High-fidelity prototypes on the other hand, are definitively representative of the final product and interactively functional. They require a significant investment of time and resources and are absolutely necessary to test final usability.

Why bother testing with Low-Fidelity prototypes?

Recently on a project with one of the big 4 banks, a senior stakeholder noticed a prototype we were testing had limited functionality. Understandably they wished to explore all possible facets of the user experience and raised the question, “Why bother testing with low-fidelity prototypes?”

Low-Fi prototypes;

- Make it easy for users to identify fundamental issues and contribute to the final design. (Dong, 2005).

- Are fast and iterative, allowing for simple adjustments on the fly based on rapid feedback from real users. (Tohidi, et al, 2006).

- Save money by avoiding expensive development commitments to a flawed design. (Sefelin, et al, 2003; Walker, et al, 2002).

Filling in the blanks

The unpolished nature of the prototypes means users are often more comfortable pointing out shortcomings in the concepts (Gerber, 2012) and more likely to avoid social desirability bias in their comments (Schunk 1984; Crimm 2010). Users can recognise lo-fi prototypes need further development and are more likely to contribute unexpected solutions. Hi-fi prototypes often seem complete which removes the opportunity for further development in the users’ mind.

Low-fidelity prototypes can ignite user imagination by asking the question ‘what could it become?’

High-fidelity prototypes, on the other hand, ask the question ‘what is wrong?’

Authenticity in user centred design.

Lo-fi prototyping provides a particular level of user insight not possible with high-fidelity prototypes. Lo-fi prototypes are best tested in the early stages of design, as an unexpected perspective from a real user may highlight a need or a conceptual flaw, leading the product or service in a new direction at a point where there is still flexibility to change.

Working in experience research, high-fidelity digital prototypes are frequently seen to miss the fundamental expectations of their users. Often this is due to high levels of motivation by developers, and pressure from executives to build a solution as quickly as possible. Testing and iterating with users can be seen as an interruption to an enthusiastic momentum.

In these cases, there is a substantial investment of time and effort before a real user has tested the concept. This significantly increases the risk of extra expenses, delays and a poor user experience. When a product launch date is inflexible, typically, by the time authentic feedback on the concept is received, it is too late to redevelop.

This is where the benefit of low-fidelity prototyping comes in, by testing early and rapidly responding to real user needs before investing weeks or months of expensive development.

This is not to say that high-fidelity prototyping is not important, we simply generate different knowledge with different modes of testing. High-fidelity prototype testing is the only way to be confident in the functionality and usability of a new product or service offered to customers.

Although low-fidelity prototyping does not have the resolution to make confident recommendations on the nuanced intricacies of the final outcome, it does create the most fertile environment to generate and test uniquely innovative experiences for users.

References

Dong, A. (2005). The latent semantic approach to studying design team communication. Design Studies, 26(5), 445e461.

Gerber, E., & Carroll, M. (2012). The psychological experience of prototyping. Design studies, 33(1), 64–84.

Grimm, P. (2010). Social desirability bias. Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing.

Schunk, D. H. (1984). The self-efficacy perspective on achievement behavior. Educational Psychologist, 19, 199e218.

Sefelin, R., Tscheligi, M., & Giller, V. (2003). Paper prototyping — what is it good for? A comparison of paper- and computer-based prototyping. Paper presented at the ACM Conference on Computer Human Interaction.

Walker, M., Takayama, L., & Landay, J. (2002). High-fidelity or low-fidelity, paper or computer? Paper presented at the Proceedings of Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 46th Annual Meeting, Baltimore, MD.

Tohidi, M., Buxton, W., Baecker, R., & Sellen, A. (2006). Getting the Right Design and the Design Right: Testing Many Is Better Than One. Paper presented at the Computer Human Interaction Conference, Montreal, Quebec.